When it comes to setting goals and accomplishing goals, we all have our predispositions. They can be a reflection of the context of the situation or the intentions of our motivations. Luckily, there is a breadth of research on the subject of goal orientation that can aid in how we approach goals and calibrate the manner, in which we attempt to reach them.

Goal Orientation research falls under the umbrella of motivation and can be a resource to anyone who is interested in enhancing their motivation by better understanding its elements.

A Brief History of Motivation Research

Goal Orientation Theory started with a scholar by the name of John Nicholls. He approached studying motivations from the angle of developing a model or a framework for achievement goals. Johns’ contribution to the subject is of a two-factor orientation model.

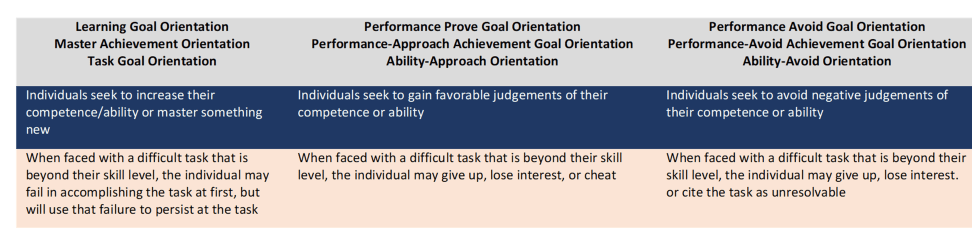

- Task Orientation: Individuals seek to develop their competence relative to their abilities (a self-referent standard)

- Ego Orientation: Individuals seek to validate their competence relative to the abilities of others (an other-reference standard)

The subject of Goal Orientation then evolved with continued research into two broad classes of goal orientation, which began with studying the concept of Learned Helplessness.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, two psychologists, Dweck, and Diener studied the behaviors of grade school children. They developed an experiment in which schoolchildren were asked to solve a set of matrix puzzles. Each child began with simple puzzles, and when they finished the puzzle they received a new one. With each new puzzle gradually increasing in difficulty. As the children made their way through the puzzles the researchers discovered something interesting about the two distinct ways the children would approach the puzzles as they increased in difficulty.

The researchers asked the children to verbally discuss how they felt and what they were thinking as they worked on the puzzles that were beyond their level of abilities. The findings split the children into two distinct groups based on their responses. Some children exhibited a helplessness response pattern in that they became upset, lost interest in the puzzle, and commented on their lack of ability (Vandewalle, 2019). In contrast, other children exhibited a mastery response pattern, in that they viewed their failure as temporary, developed new problem-solving strategies, and reported enjoying the challenge of working on the more difficult puzzles (Vandewalle, 2019).

The fascinating part of the findings was the difference between the responses of the children being a reflection of their motivation by different goals. The children that responded in a helpless manner, were believed to have held performance goals and were preoccupied about the potential appearance of having low ability (Vandewalle, 2019). While the other group of children who exhibited a mastery-oriented response pattern may have held learning goals, and their engagement with the puzzle-solving challenge may have superseded concerns about the appearance of low ability (Vandewalle, 2019).

As the research in Goal Orientation continued to evolve the importance of focusing on motives vs. worrying about personality traits came to light. In other words, this is the difference between an individual’s motivation for validating a personal capability (i.e. proving to be intelligent) or an individual’s motivation about developing (such as growing intelligence). Which proved to be vastly different approaches.

Dweck and Diener developed two broad classes of underlying goal orientations.

- Learning goals in which individuals seek to increase their competence, to understand or to master something “new”.

- Performance goals in which individuals seek to gain favorable judgements of their competence to avoid negative judgements of their competence.

In other words, individuals can engage in learning goals with a focus on ability development or performance goals with a focus on ability demonstration.

Further research built upon these two broad classes of goal orientations. However, to simplify I have combined the school of thought.

Context and Task Complexity

If you take the time to review the research it seems overwhelmingly obvious that having a learning goal orientation is far more valuable for achieving one’s goals than any other orientation. However, context does matter.

If a task is complex and challenging, then a Learning Goal Orientation is superior. However, if a task is simple then a Performance Goal Orientation is superior.

If a task is high in rule consistency then Performance Goal Orientation is superior. However, if a task is low in rule consistency then a Learning Goal Orientation is Superior.

Finally, the culture in which the individual is part of matters. Obviously, for a learning culture, a learning goal orientation is superior. In a performance-driven culture, then learning goal orientation or performance goal orientation is effective.

Why is this interesting?

Understanding motivations and our own predisposition to a goal orientation can help us understand the psychological barriers we manifest that hold us back from our potential and developing the depths of our talents.

If we are operating from the orientation of Performance Goal or Performance Avoid, then our behaviors and beliefs can sabotage our opportunities to develop to our potential. Take, for example, the concept of Implicit theory, which is a belief about the controllability that one has over personal attributes such as intelligence, interpersonal skills, and personality (Vandewalle, 2019). At one end of the spectrum, we have individuals who believe their intelligence is fixed, while at the other end of the spectrum individuals believe their intelligence can be expanded upon. Two vastly different systems of beliefs, where the latter individual’s belief system will alter their behaviors and the task/goals they set for themselves. Which in turn will influence the development of their talents.

In addition, Learning Goal Oriented individuals believe that effort is more valuable than ability. While performance-oriented individuals believe the opposite. Over time, we can see how the former will have the advantage of developing their skills and talents. Performance-Oriented individuals can run into a development barrier with the belief that exerting significant effort could signal a lack of ability because an individual with high ability would not have to exert so much effort to succeed (Vandewalle, 2019). Learning Oriented individuals believe the opposite.

Another interesting barrier to talent development is the concept speed of knowledge acquisition, the degree to which one believes that learning is a gradual process of expending effort over time or that learning occurs either quickly or not at all (Vandewalle, 2019). Learning Oriented individuals subscribe to the gradual process of learning. This is specifically important to the development of challenging skills and reaching the inner depths of our potential and talents. Many times, on our journeys of development we fall short, or “fail”. How we respond is much more important than the judgment of that moment in time. The ones that respond in a learning manner, have the opportunity to become masters of their craft, the ones that do not, focus on the outcome, and miss the lessons of the experience. The fear of failure far too often is the barrier that holds back the worldly talents of many and has a positive relationship (statistically) with both performance-proven and performance avoid orientations (Vandewalle, 2019).

Our goal orientation provides us the courage, confidence, and motivation to try and continue to try things that are beyond our abilities at the time. We can develop our abilities and reach the depths of our talents by doing tasks that challenge us. Our perceived abilities and self-efficacy can be of great value to unleashing our talents or can be our greatest barrier in preventing us from doing so. Our orientation of how we approach goals, and our judgments of the outcomes are something that we can begin to nurture simply by being aware of them and calibrating along the way.

Take the time to be observant of your goal orientation to better understand your motivations and how you work. It is imperative to unleashing the talents within.

The cave you fear enter holds the treasure you seek

J. Campbell

References:

Vandewalle, D., Nerstad, C. Dysvik, A. (2019). Goal Orientation: A Review of the Miles Traveled and the Miles to Go. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6:115-144